Meet the People Facing Trump’s Budget Cuts

In President Donald Trump's first budget, he proposed a series of changes to federal spending that included deep cuts to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Specifically, he targeted the Community Development Block Grant program, which steered money to local agencies to fund projects that would help low- and moderate-income Americans. The Trump administration argued the program was "not well-targeted to the poorest populations and has not demonstrated results." For The New York Times National desk, I traversed the country to speak to real people whose lives had been affected by the program.

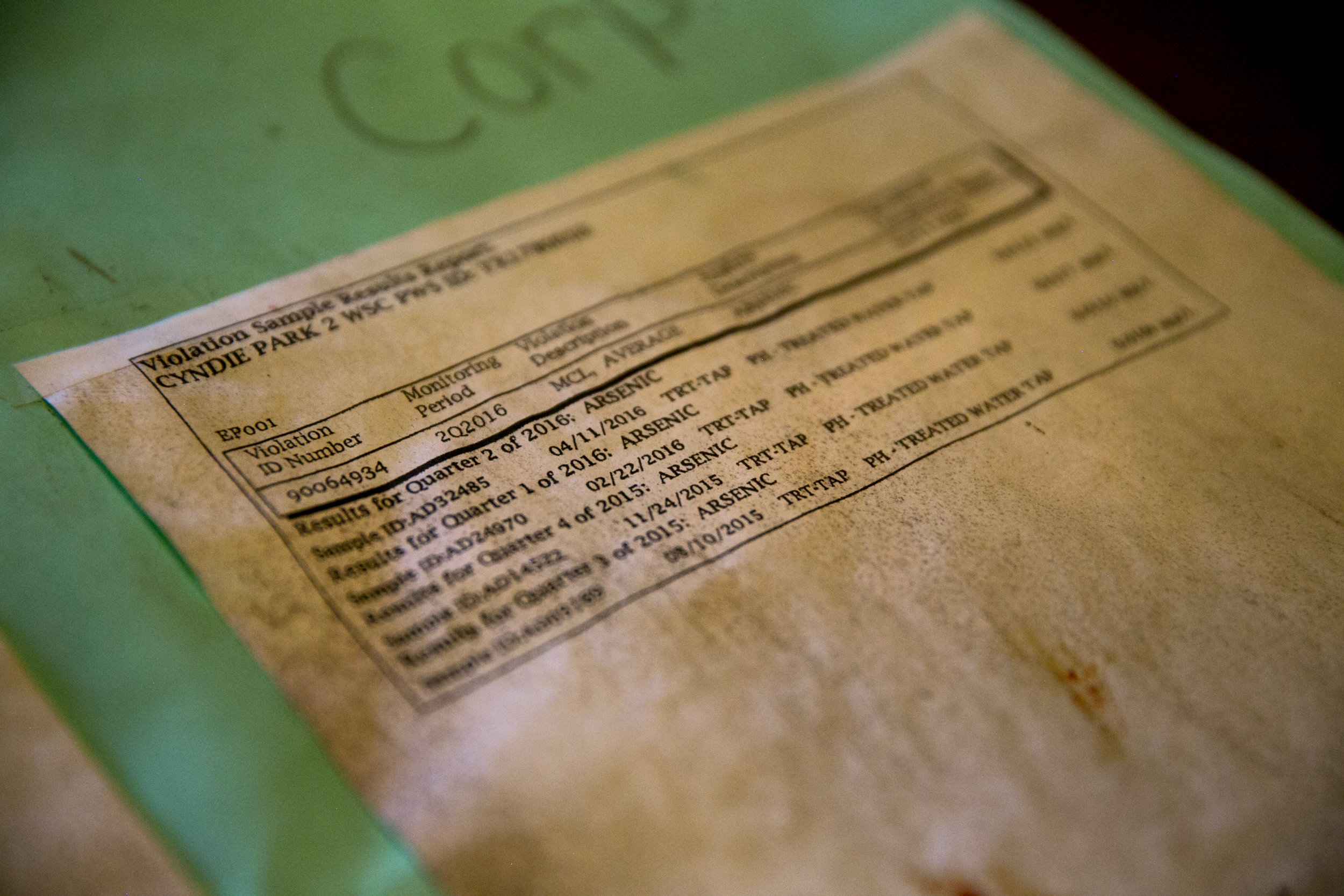

The Gonzalez Family; Cindy Park, Texas

“It’s like we are living in a foreign country and we don’t have the luxury of turning on a faucet”

Ruben Gonzalez' and Lucia Rodriguez' front yard looks straight out of a movie about down-home Texas.

After being greeted by the sight of a clay bull skull above the front door, you take in the smell of smoke billowing from the charcoal barbecue and the laughs of the couple’s children from the backyard, pushing each other down mounds of dirt in a hulking slice of water piping or taking a crack at a slow-pitched baseball.

The property, which has been in Rodriguez’ family for a long time, is in the colonia neighborhood of Cindy Park, which is a mile-long, straight, flat road running through Robstown, Texas, near Corpus Christi. For decades, the residents here have had their water supplied by either private wells on their own property or by a well operated by the Cyndie Park II Water Supply Corp.

That well has tested for years with levels of arsenic that don't meet EPA standards and, even though they installed a filtration system in 2014, reports submitted to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality as recent as January 2017 show arsenic levels exceeding the standard of .010 mg/l.

Ruben Gonzalez' (left) community will soon have potable water, funded in part by the CDBG program. He also got a job installing the pipeline.

A solution to the neighborhood's water challenges is on the way. The communities have received three major grants that will soon connect them to potable water: 2 CDBG grants of $500,000 to build distribution lines in Cindy Park and Ranch — an adjacent colonia — and, just this past week, a $900,000 from the Texas Water Development Board to build the transmission line that will bring the water to the distribution lines.

In the meantime, Lucia Rodriguez’ family is still purchasing bottled water for drinking.

On a recent Sunday, the family loaded into Ruben’s station wagon to head into town for lunch and a few errands. Rodriguez brought along a trash bag full of empty gallon-sized water bottles. After a stop for lunch at a local Whataburger, Rodriguez dropped her husband and two boys off at the local skate park. She and her daughter Roxane headed to a nearby HEB where she dropped change into a windmill-themed dispenser and filled the bottles one-by-one. When she got home, the kids carried the gallon jugs back into their home and then ran back outside to play, waiting for the family barbecue to begin.

Rodriguez in the backyard of her family's home.

The kids play in the backyard inside a piece of piping used in water transmission lines like the one being hooked up to their neighborhood.

Rodriguez, who serves as the secretary of Cyndie Park II Water Supply Corp.’s well, went to check out the well. When she arrived, she was surprised to see yellow and white marks running down the side of the large blue tank used to remove the arsenic from the water. The operator told her that there had been a small leak, but she said she was concerned about how long it had gone on. While it wouldn’t necessarily affect the quality of the water in the short term, it illustrated just how challenging it is to maintain a well of this age.

A drip of water comes from the family's tap. They use it for cleaning, but not for drinking.

Ruben Gonzalez and his daughter sit on the front porch of their home.

“I have goosebumps, and I get so emotional thinking about if we don’t get this funding and the amount of people who are going to die.”

Kimberly Phillips; Bethlehem, New Hampshire

Since she began snorting prescription Ritalin at the age of 11, Kimberly Phillips has been locked in a battle for her life.

In northern New Hampshire, along the Ammonoosuc River, she's joining others struggling with addiction work toward recovery in a six-decade-old cottage that is not up to code. Friendship House, the only residential drug treatment center within 65 miles, is relying on money from the Community Development Block Grant program to complete a new building by October 2018 that meets code requirements so that the center can continue to provide services. Without the money, the center may not be able to stay open

Residents at Friendship House struggle with addiction - some to alcohol and many to opioids, which claim many lives in rural New Hampshire.

Facilities like Friendship House are few and far between in Northern New Hampshire, where opioid abuse and overdoses run rampant. "There are not enough resources up here," Phillips says. "And that's why people are dying."

Track marks run up Phillips' arms as she plays poker with the men in the facility. She describes herself as a “chronic relapser” and attributes a lot of her past failure to get sober to alcohol, which she assumed she could use in moderation. “Alcohol always leads me back to drugs," she says. "And it’s going to kill me.”

Garry Goff; Peru, Indiana

“I felt like I was lost and I felt like I was a loser.”

At 58 years old, Goff embodies much of what the “middle of the country” is about, particularly for what is increasingly becoming a bygone generation. He married his high school sweetheart, Patty, 37 years ago. They have two children, a boy and a girl. They have a dog and a cat. They have a fence — not white picket, but iron rod. And, for a long time, Goff ran a family business in Kokomo, Indiana, the town where he grew up.

At one point Goff’s body shop employed 8 people — workers he was proud to keep fed. But when the recession hit, Kokomo was not immune and Goff’s business became a casualty of a depressed economy. He eventually laid off all of his workers and shut the doors to his shop, save for a few custom jobs he does for old friends.

Goff was worried. Worried about his mortgage. Worried about his family’s future. He sold his boat and other possessions to pay his bills. He teetered on the edge of foreclosing on his home. And right about that time was when the Dean Baldwin facility opened up in Indiana. Goff got an entry level position. “That saved our lives,” his wife Patty said, describing it as a blessing from God.

Dean Baldwin's facility is situated at the Grissom Aeroplex and opened after being renovated in part with $2 million in Community Development Block Grant funding. As a child, Goff used to watch military planes fly overhead at the Grissom Air Reserve Base during air shows and trainings. Now, the rebirth of the site has also meant a rebirth in his career. He's moved up from his entry-level position at the company and it's helped stabilize his family's income. “That saved our lives,” his wife Patty said, describing it as a blessing from God.

Goff's team strips the planes bare and then puts a custom paint job on them.

Although he initially was uninterested in managing others after his business had fallen apart, Goff eventually moved up in the ranks and now manages a bay full of workers painting planes like A330s and 747s for major airlines.

While other workers often head out to purchase lunch, Goff usually sits in his car and calls his wife, Patty, who prepares a packed lunch for him.

At home, Patty and Garry prepare to head out to dinner after a long day's work.

Jennifer Coulter; Hollister, California

“I’ve worked hard. I’ve gone to counseling. I do everything possible, you know? And in the end, I’m still stuck out here. I don’t want to die out here.”

It was time for Jennifer Coulter to go home.

For weeks, she’d been living behind a Taco Bell on San Felipe Road in a dusty, dry homeless encampment where graffitied freight trains run by and a man in the parking lot is making art out of old tires. Today, she's moving from there to a drought-dry river bed, where she stayed before the county cleared the makeshift community ahead of flooding.

Despite a homeless population that has surged from 193 to 651 from 2011 to 2015, the County of San Benito has no permanent homeless shelter for people like Coulter.

But with $3 million from the Community Development Block Grant program, the county is planning to convert an old machine shop into a 50-bed permanent shelter that will also feature a service center to help residents like Coulter escape homelessness.

Lately, Coulter had grown tired of living behind the Taco Bell. She said it was trouble. And she missed what the other side of town had to offer. “It’s been months since I’ve been home,” she said.

Coulter greets her friend Daniel Estrada, who she wound up staying with in the encampment later that evening, as she moves her belongings to the river bed.

Coulter's friend Patricia Arballo, 53, explored the river bed where they used to live, looking for old belongings.

Until the grant funding for the shelter comes through, Ms. Coulter will continue spending her days on the streets, occasionally taking refuge in a friend’s garage and in her music. She often blares ’60s rock.

In the garage of her friend Tom Tucker, she cranked the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter,” singing along and tilting her head skyward:

The floods is threatening

My very life today

Gimme, gimme shelter

Or I’m gonna fade away